By Helen Sharp

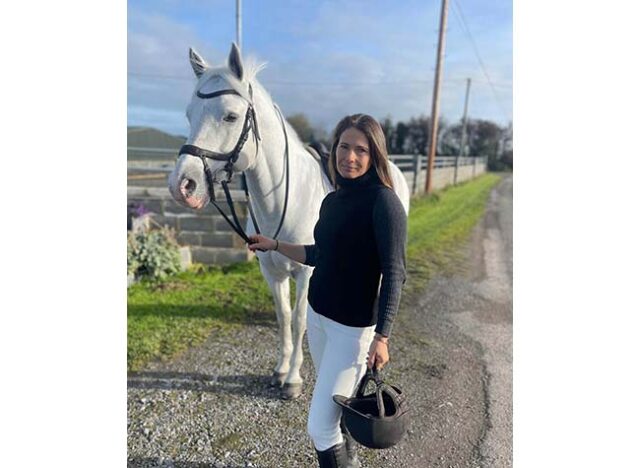

Photography: Private collection

Few people understand how tough it is to be an equine reproduction vet. The job is physically and mentally testing and there is a distinct physical risk to safety. Equine reproductive veterinarian Kate Murray shares a frank discussion with Helen Sharp about the toll her job can take and her strategies to overcome it.

According to Murray, the amount of knowledge, experience and skill required to achieve as many first cycle pregnancies as possible adds enormous pressure to an already exhausting job. Murray is based in Four Mile House, Co Roscommon, Ireland, and reveals a brutal schedule during the breeding season: “The physical act of scanning or inseminating the mare is the easiest part, the decision-making based on findings, and history of the mare is the real work. Additionally, time-wise, what I need to pack in a day to get everything done on time is almost too much. The morning jobs to be done before breakfast alone are so many; scanning mares for frozen semen at 6:00 a.m. (around 10 mares every six hours) followed by scanning mares for imports, collecting stallion semen for shipping, plus the yard has to be fed and cleaned. It’s so much, and we’ve no staff. It’s just my husband Keith, the farm manager, and our daughter Eva in the summer. Our son Keelan has a full-time job now: It’s a huge loss to me.”

After breakfast, Murray then needs to scan the resident herd of mares: Usually between 50 and 60 mares, minimum to be brought in from the field before any outpatient mares arrive. “That's why we don't want any outside mares in the yard until 11:00 a.m. By noon I need to scan frozen cycle mares again and grab some lunch; in truth, breakfast generally doesn’t happen. I then continue with the resident mares, those stabled, then need to collect semen from the stallions for resident mares and do whatever jobs transpired since morning. By then, it’s time for evening outpatient scanning and frozen cycles again at 6:00 p.m., and outpatients continue.”

For most professions, the day would be winding up. Still, for Murray, the evening yards have to happen somewhere in the meantime, and she may get to eat dinner around 10:00 p.m., but by midnight she is back in the clinic to scan frozen cycle mares again to check where they are in their ovulation cycle. “That’s seven days a week, March to September,” she states. “It’s really straining, nerves get frayed, and things must run smoothly, otherwise, it can get overwhelming. I get to eat two meals [a day] and get to sleep a bit, but not nearly enough. I rarely get a few minutes to relax and do something else for a while.”

With a schedule as relentless as Murray’s, self-care becomes a survival technique as opposed to a luxury, and she explains: “Structure is essential for my wellbeing, not doing everything at once, and knowing that I’ll get finished in time to eat and sleep. That’s why we try to do outpatient mares at designated times, as otherwise it throws a spanner in the works, or someone drives in just as I sit down to eat, and that’s not comfortable. Even if I don’t get time off, it’s essential to have a peaceful time to eat when clients can’t reach me on the phone – so calls at 11:00 p.m. or 6:00 a.m. are not being answered... To read the complete article you need to be a subscriber

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO BREEDING NEWS

SUBSCRIBERS CAN READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE BY LOGGING IN AND RETURNING TO THIS PAGE