By Janet Douglas, Roly Owers and Madeleine L.H. Campbell

Most societies regulate human activities using laws that state clearly what is, and is not, legally permissible. However, there is a second layer of permission that is granted – or revoked – by the public. This second layer is known as a ‘social licence to operate’ (SLO)...

It represents an intangible, implicit agreement between the public and an industry or group. The public may approve of an activity, in which case it can proceed with minimal formalised restrictions, or it may disapprove, and this may herald legal restrictions, or even an outright ban.

This review discusses the concept of SLO in relation to equestrianism. Experience from other industries suggests that, to maintain its SLO, equestrianism should take an ethics-based, proactive, progressive, and holistic approach to the protection of equine welfare, and should establish the trust of all stakeholders, including the public. Trust will only ensue if society is confident that equestrianism operates transparently, that its leaders and practitioners are credible, legitimate, and competent, and that its practice reflects society’s values. Earning and maintaining this status will undoubtedly require substantial effort and funding – inputs that should be regarded as an investment in the future of the sport.

Abstract

The concept of ‘social licence to operate’ (SLO) is relevant to all animal-use activities. An SLO is an intangible, implicit agreement between the public and an industry/group. Its existence allows that industry/group to pursue its activities with minimal formalised restrictions because such activities have widespread societal approval. In contrast, the imposition of legal restrictions – or even an outright ban – reflect qualified or lack of public support for an activity. This review discusses current threats to equestrianism’s SLO and suggests actions that those across the equine sector need to take to justify the continuation of the SLO. The most important of these is earning the trust of all stakeholders, including the public. Trust requires transparency of operations, establishment and communi-cation of shared values, and demonstration of competence. These attributes can only be gained by taking an ethics-based, proactive, progressive, and holistic approach to the protection of equine welfare. Animal-use activities that have faced challenges to their SLO have achieved variable success in re-establishing the approval of society, and equestrianism can learn from the experience of these groups as it maps its future. The associated effort and cost should be regarded as an investment in the future of the sport.

1. Introduction

The concept of ‘social licence to operate’ (SLO) first arose in 1997 in relation to mining[1] and has since been extended to other natural resource management industries such as fishing, forestry, and energy production[2]. The concept is also relevant to animal-use industries and activities, including dairy and sheep farming, wildlife use, zoos, hunting[2], circuses[3], marine mammal parks[3], and equestrianism[2,4,5,6,7].

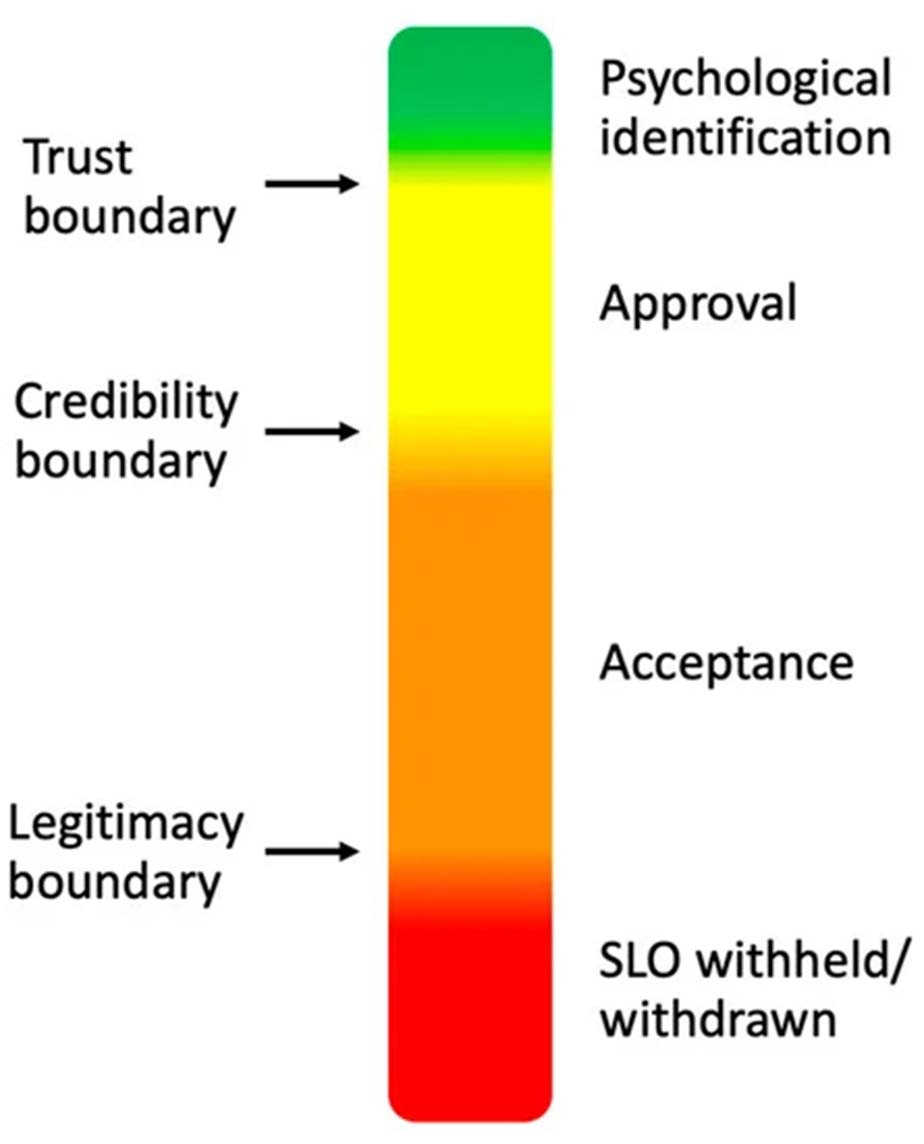

A social licence is said to exist when an industry or activity has the ongoing acceptance or approval of society[8], and it allows industries ‘the privilege of operating with minimal formalised restrictions’[9]. Social licence is not an ‘all or nothing’ phenomenon, and public acceptance of an activity can sit at any point on a continuum from psychological identification with the activity to outright rejection[8] (Figure 1).

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO BREEDING NEWS

SUBSCRIBERS CAN READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE BY LOGGING IN AND RETURNING TO THIS PAGE