By Kim A. Sprayberry DVM. MaKristina G. Lu VMD

Photography: Individually captioned

Including injuries in stallions, injury of the external portion of the reproductive tract and gestational conditions in the mare

In the gamut of reproduction-related emergency conditions in horses, dystocia in the mare may be the problem most familiar to equine veterinarians and horse owners – the specter of birth-related problems rightfully elicits much preparation and client education from veterinarians to recognize and prepare for parturition-related emergencies – but there are many other conditions affecting the reproductive tract that also represent significant problems in which timely intervention is imperative. As with emergencies involving any other organ system, minimizing the time to diagnosis and intervention is key to a positive outcome. Therefore, the ability to recognize and intervene in these conditions is an important part of the knowledge base for veterinarians whose practice includes breeding animals.

This article will review guidelines for managing selected emergency conditions involving the reproductive tract in stallions, and that involve the external portion of the tract or arise during gestation in mares. The goal is to help prepare the veterinarian to recognize and confidently undertake or at least initiate effective interventions for these problems in the field.

(Courtesy Dr. Peter Morresey, BVSc MVM MACVSc DipACT DipACVIM CVA, Kentucky.)

External portion of reproductive tract of mares: Injury of the vestibule and vagina

Lacerations of the vagina, transverse fold, and vestibule most commonly occur during breeding and foaling. The vulva and vestibule are also an occasional site of injury from kicking wounds from other mares; the hind foot of the kicking mare can abrade and lacerate the vulva and enter the vestibule and tear the mucosa (Fig. 1). Mares found with vulvar injury should be examined to determine whether abrasion or laceration extended into the vestibule.

Blood on the stallion’s penis or in a dismount sample after natural-cover breeding may be the initial indicator of reproductive tract trauma1 and should prompt immediate examination. Blood in a dismount sample may also originate from an episiotomy performed in the mare to facilitate breeding. Breeding injury often takes the form of laceration of the cranial part of the vagina, in the dorsolateral aspect of the wall near the cervix, but may also also result in full-thickness rupture of the wall or laceration of the uterine wall.1 Methods of examining the vagina and vestibule include manual palpation; visualization of the tract through a disposable or glass speculum as it is gradually withdrawn from the cervix to the vestibule; evaluation with a Caslick speculum, which can allow a broader visual field, especially of the cranial extent of the vagina; and use of an endoscope that is passed manually or through a speculum.

If vaginal injury is suspected after a live breeding, initial evaluation can be performed with a speculum or endoscope to confirm a lesion and site. Injuries involving only the mucosa or submucosa often heal spontaneously. Injuries that appear suspicious for deeper penetration may be best evaluated with a scrubbed and disinfected bare hand, lubricated with sterile jelly, and slowly and gently advanced into the vagina for careful digital exploration in the adequately restrained mare. Deep lacerations or full-thickness tears in the cranial aspect of the vagina are likely to open into the peritoneal cavity and warrant immediate emergency care, including administration of antimicrobials and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), and preparation or referral for surgery, if possible.[1,2,3]

Diagnostic workup for peritonitis, and monitoring for it over the next several days, with peripheral blood testing, sonographic imaging, or abdominocentesis is also indicated.

It should be kept in mind that deep lacerations or near-ruptures that approach but do not actually penetrate the serosal surface can still facilitate translocation of bacteria and induce peritonitis and the same clinical changes as a true perforation. Vaginal lacerations and perforations arising caudal to the peritoneal reflection can be managed with medical treatment and second-intention healing. In one report[4] of cranial vaginal lacerations and caudal uterine lacerations repaired with the mare in a Trendelenburg position, five of eight mares with vaginal laceration recovered, whereas two of four mares with uterine lacerations were euthanized because of severe, diffuse peritonitis. If the equipment and technical support are available on site for general anesthesia and hoisting the mare’s hindquarters into the Trendelenburg position, this surgery can be performed in the field if surgical expertise is available.

Lacerations in the cranial part of the vagina can also arise as a foaling injury, with clinical signs appearing in the postpartum period and ranging from mild, bloody vaginal discharge to peritonitis and intestinal evisceration through the vagina or vulva. Mares with bloody discharge and signs of systemic illness (depression, pyrexia, strong digital pulses) should not have uterine lavage until they have been examined to rule out a vaginal or uterine perforation.

Summary: Suspicion of a vaginal injury should prompt visual evaluation of the tract to locate a lesion, and possibly manual evaluation to determine the site and depth of the injury. Deep lacerations of the uterus or cranial part of the vagina carry a risk of communicating with the peritoneal cavity; these wounds and outright perforation should be sutured and the mare treated with broad-spectrum antimicrobials and anti-inflammatories while being monitored for peritonitis. Caudal lacerations or perforations may be manageable with medical treatment.

External portion of reproductive tract in stallions:

Traumatic injury to external genitalia

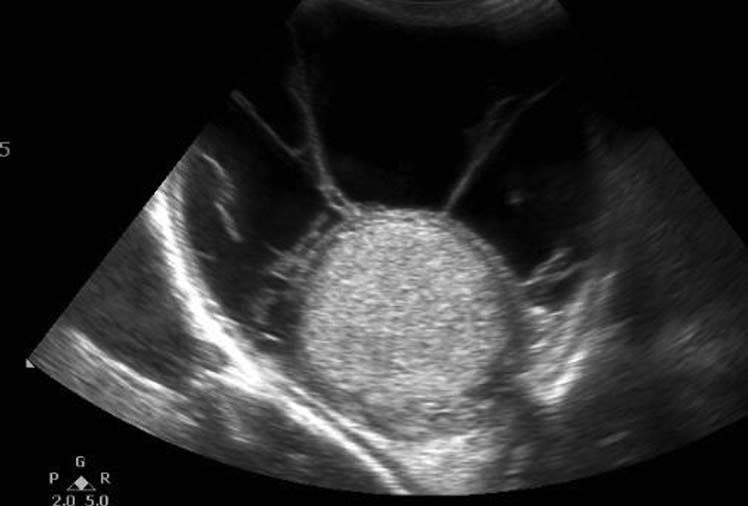

stallion following previous traumatic injury in the scrotal area. Notice the strands of fibrin extending from the surface of the testicle to the parietal layer of the tunic.

Traumatic injury of the external genitalia in a stallion is considered a reproductive emergency because prompt intervention is required to reduce damage to fertility or breeding ability. Most such injuries arise during breeding from a kick by a mare,[5,6,7] but stallions can also sustain injury to this area while attempting to jump a fence or by impaling accidents at pasture. Scrotal swelling, asymmetry, or heat, skin abrasion or laceration, and pain upon palpation make the diagnosis visually straightforward. In addition to traumatic orchitis, less-acute causes of testicular inflammation, such as septic orchitis,[8,9,10] may also be considered emergent in nature once they are noticed in a breeding stallion, because of the need to quickly and effectively reduce scrotal inflammation in the interest of preserving fertility... To read the complete article you need to be a subscriber

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO BREEDING NEWS

SUBSCRIBERS CAN READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE BY LOGGING IN AND RETURNING TO THIS PAGE