By Judy Wardrope

Photography: Judy Wardrope

The equine eventer contemplating its ultimate design has a lot to consider. The sport is demanding and requires more than a single ability, especially as the levels escalate. Chances are the competitively-minded eventer would choose a compromise: some dressage talent combined with substantial ability to run and jump. The horse’s decision would probably hinge on the fact that most of the injuries in the sport occur outside the dressage and jumping arenas.

Like the top competitors, the lower-level horse will want a design that allows for function within a comfort zone and a career that lasts a long time.

The hindquarters

Knowing the demands of the sport, the horse would most certainly opt for a strong transmission. Although the lower-level horse may not need as much athleticism as the international horse, it would not deliberately choose to have an LS gap rearward of athletic limits.

The best rear triangle for today’s sport, especially at the upper levels, is one that combines dressage, jumper and eventer traits. The equine designer would opt for a slightly shorter ilium side and a low stifle placement. Unfortunately, the trade-off is that the lower stifle makes sustained collection more difficult.

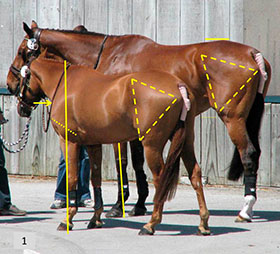

Both horses in Photo #1 show low stifle placement. In the pony, we find a slightly shorter ilium and the longest side of the rear triangle from point of hip to stifle protrusion, which is common among top eventers as well as among jumpers that excel in jump-offs. Despite being short in stature (14.2hh/147cms), his hindquarters were ideal for eventing and he proved that on the international stage.

Horse #2 also has a similar hindquarter, and he evented at the international level well into his teens.

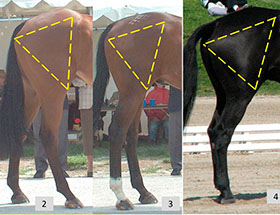

Some eventers might choose an ilium side and femur side of equal length even if the dressage phase would be more difficult. Horse #3 is built this way and completed some of the toughest 4* events before retiring in his late teens to become a schoolmaster. His stifle protrusion is well below sheath level, which resulted in a long stride and excellent scope. He also shows the longest side of the rear triangle being from point of hip to stifle protrusion.

However, the self-constructing equine would never select the femur side as the shortest side of the rear triangle, no matter the level of competition desired...

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO BREEDING NEWS

SUBSCRIBERS CAN READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE BY LOGGING IN AND RETURNING TO THIS PAGE

Photo #4 shows an eventer with a shorter femur, which explains why this horse moved with his hocks further behind him and with less of the rear stride reaching underneath him. This construction adds to the risk of hind leg unsoundness and limits the scope normally established by stifle placement. To further complicate things, we see that the ilium side is equal in length to the side from point of hip to stifle protrusion, meaning that he would have less ability to jump from an open gallop. His preferred method of jumping would have been to slow and coil, but that would adversely affect the ability to make the time on cross country. He was euthanized on course after striking several fences in a row with his hind legs/feet before dropping his shoulder in order lift the hindquarters at a wide fence on cross country.

The forequarters

No matter the desired class of competition, the horse would not choose to be heavy on the forehand since all aspects of this discipline are easier for the horse that is light on the forehand.

If given the choice, the eventer would have the line depicting the pillar of support emerging well in front of the withers, the point of shoulder would be high and the base of the neck would tie in well above the point of shoulder for increased lightness of the forehand.

And for longevity, the eventer would opt for the bottom of the pillar emerging into the rear quarter of the hoof. Again, the level of competition would not matter to the horse when making this architectural decision.

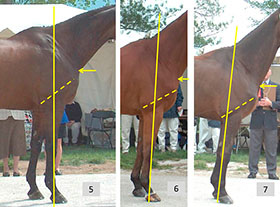

Horse #5 has a pillar of support that emerges well in front of the withers and well into the rear quarter of the hoof. He also shows a fairly steep rise from elbow to point of shoulder, which aided in his ability to be quick with his knees over fences as well as adding another factor for lightness of the forehand. And, his base of neck is well above a high point of shoulder.

Horse #6 has a pillar of support that emerges well in front of the withers and well into the rear quarter of the hoof, but he shows less rise to the humerus than #5, which is why stadium was his nemesis. On cross country, he had to put more effort into lifting his forehand to compensate for knees that were not as tidy as those of #5. His base of neck is well above a not-as-high point of shoulder, negating any additional lightness to the forehand, meaning neutral in that regard.

Horse #7 has a pillar of support that does not emerge quite as far in front of the withers as on the other two horses, so he did not gain quite as much lightness to the forehand. It also emerges behind the heel, which added to his risk for damage to the suspensory apparatus of the lower limb. We also see a fairly steep rise to the humerus, meaning he was tight and fairly quick with his knees over a fence and had that factor for lightness. His base of neck is well above a high point of shoulder, adding another factor for lightness. Given his risk factor (bottom of pillar), he needed all the lightness of the forehand he could get. Sadly, he broke down on cross country and was euthanized as a result of the damage to the front leg after the suspensory apparatus was so compromised that bones gave way with each additional stride he took.

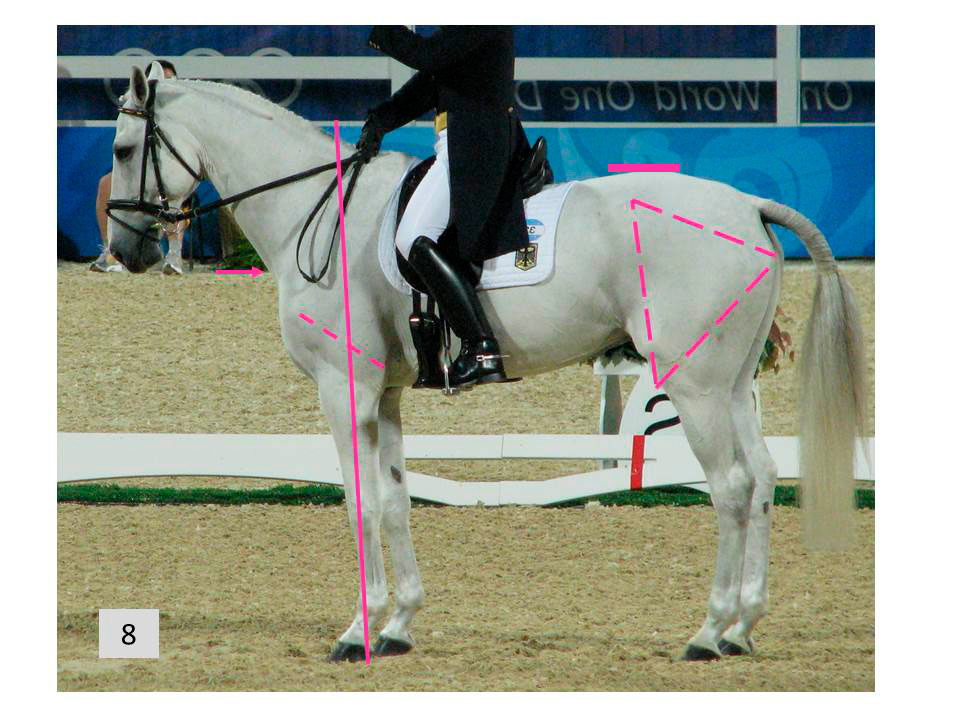

Structurally, Horse #8 displays what one would expect in a self-designed eventer. Like all the top equine athletes, he has excellent LS placement. It can be seen at work in the photo of him jumping.

His stifle is well below the level of the sheath, and the range of motion/long stride is evident in the trotting photo and the scope is evident in the jumping photo.

His rear triangle measures slightly shorter on the ilium and the longest side is from point of hip to stifle.

His pillar of support emerges well in front of the withers and into the rear portion of the heel. His humerus shows a substantial rise from elbow to point of shoulder, and the base of the neck ties in well above the point of shoulder.