By Adriana van Tilburg

Graphics: HoofStep app

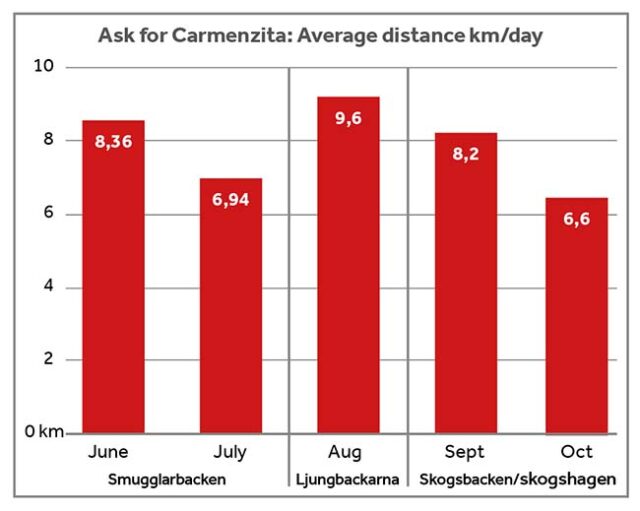

In 2019, a high-profile pilot project was carried out in Sweden on Brösarp’s slopes with young, future competition horses in jumping. The group was followed for six months, and systems were tested to monitor their welfare. The purpose was to measure the effect of raising young horses on wide, hilly lands from a sustainability perspective.

The Brösarp project resulted from discussions with former equine vet and biomechanics expert Professor Ingvar Fredric Fredricson (former head of Sweden’s national studfarm, and father to Olympian riders Jens and Peder) about the importance of equine sustainability and how much horses move during the first three years of life. In November 2022 (issue #311), Breeding News published an article that outlined the launch of the project.

In a primary step, researchers chose to study how a group of young and relatively untrained jumping mares would integrate into an existing herd of Icelandic mares and cope in demanding terrain. Jens Fredricson and his colleagues provided six one- and two-year-old jumping horses for a pilot trial.

According to Ingvar Fredricson, it has long been known that ample movement during foalhood and beyond contributes significantly to long-term soundness. “My main goal is to make horse breeders aware that young horses allowed to move over large areas with varied footing grow into strong and resilient individuals,” he explains. “The early years – perhaps even just the first few months – are critical. The window of opportunity is small. Foals need to use their hooves and legs during the first three months to develop strong cartilage, while the skeleton, ligaments, and joints continue developing until the horse is around two-and-a-half years old. If a young horse stands mostly on soft straw during this period, it will develop only thin joint cartilage. And what is missed during this time cannot be made up later.”

Fredricson continued by explaining; “A poorly raised horse cannot be improved later. It may look like a million-euro horse, but it will remain a weak individual and will never fully realize its genetic potential.”

Hästen i Skåne (see box on next page from our 2021 article) wanted to investigate through collaboration with other stakeholders how young horses develop if they are given the opportunity to move freely on very large and hilly lands with varying surfaces. A natural environment means that the horse strengthens physically through movement and thus feels better both physically and mentally. In a free/natural environment, horses eat evenly throughout the day, over a total of eight to 12 hours. During the day, grazing alternates with activity/rest; at night, grazing alternates with sleep/rest.”

Three seasons of monitoring and data collection have now led to a clear conclusion: raising young horses in open, hilly terrain may hold significant benefits for their long-term soundness and development.

The horses in the Brösarp project were reported to be in excellent health. They moved extensively across varied terrain, had continuous access to grazing, and showed no signs of limb injuries – despite galloping [voluntarily] up and down steep slopes. These findings suggest improved body awareness and musculoskeletal resilience, potentially laying the groundwork for more durable sport horses in the future.

What can used from the research?

The Brösarp study also highlighted the importance of horses’ natural eating behavior, emphasizing this as a key takeaway. Horses are obligatory herbivores with small stomachs. Both their digestive system and their behavioural biology are adapted to eating roughage for between 15 and 18 hours per day. To benefit from good health and welfare, this means that they need to eat often, rather than having large meals infrequently. Horses that are forced to go long periods on an empty stomach risk developing issues such as colic and stomach ulcers. If they do not have an outlet for their chewing needs, they are also at risk of becoming aggressive or developing stereotypies or other problem...

CLICK HERE TO READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE IN THE ONLINE EDITION OF BREEDING NEWS