By Dr. Mariette van den Berg, B.AppSc.(Hons), MSc., PhD (equine nutrition)

Photography/Graphics: MB Equine Services

While there may be countless reasons why we have horses in our lives, and for most of us there is more than one reason, it is the relationship with our horse(s) that truly drives our interest and equestrian endeavours (be they personal or professional).

Having this relationship is motivation and reason enough, whether we breed horses, compete, or never step in the ring and ride just for fun. As such we all attempt to take steps to refine this human-horse relationship and ensure that our horses are well looked after, healthy, and ‘happy’.

A horse’s well-being is based on its physical, emotional, and physiological states. Most horse owners will endorse that when horses are healthy, and ‘happy’, they also perform better. In addition, equine well-being is a very important issue with regard to public perception, as well as the extremely meaningful ethical issues. Most recently, the global discussion prompted by the well-being of horses that were ridden in modern pentathlon during the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. As such, equestrians and observers of horses should be able to determine if a horse is healthy and in good condition both physically and mentality.

Assessing a horse’s well-being

But how do we know if horses are doing well, are looked after, healthy, and even feel happy? As humans we often take a very anthropomorphistic approach to our vision of how our horses are doing, and their lifestyle circumstances. Anthropomorphism can be defined as the “attribution of human mental states (thoughts, feelings, motivations, and beliefs) to non-human animals”. We are exposed to this on a daily basis, just thinking of how we create and watch movies or cartoons with animals that have human traits. We also apply it daily when it comes to our animals: When we say our horse is happy, we don’t truly know what they are feeling, but we are interpreting it based on what we see as happy body language and what we perceive as a happy stimulus. For example, when you move a herd of horses into a new grassy paddock after being stabled, horses run around, may exhibit playing behaviour and excitement such as rearing and bucking. So, a lot of the time we are not far off the mark – horses are free-roaming and grazing herbivores – so when we say our horses are ‘happy’ when they go outside into the paddock, we are probably correct.

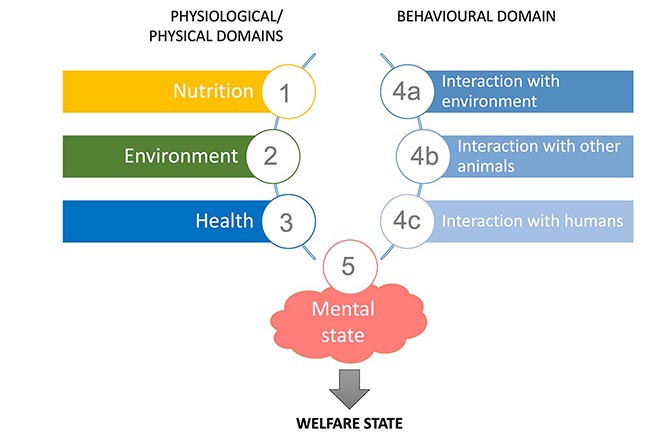

from Mellor et al. 2020. New presentation of the Five domains model with a breakdown of behavioural interactions. The model consists of five areas or domains that focus attention on specific factors or conditions that may impact on an animal’s welfare:

1) nutrition, 2) environment, 3) health, 4a-c) behavioural interactions with environment, other animals, and humans and 5) mental state (Ilustration by MB Equine Services).

But there are times when anthropomorphism can become dangerous and hinder us from doing the best thing for our animals. This is because anthropomorphism is based on assumptions and can lead to an inaccurate understanding of biological processes in the natural world. Anthropomorphism has led many owners to overfeed their horses and/or other pets. It has also led them to provide animals with food items and diets that are unhealthy. Another example is ‘over-rugging’ horses, thinking they are cold because we feel cold... To read the complete article you need to be a subscriber

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO BREEDING NEWS

SUBSCRIBERS CAN READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE BY LOGGING IN AND RETURNING TO THIS PAGE