By Sonja Egan

Photography: Mirko Sajkov

Graphicsa: Sonja Egan

The efficient movement of horses and biological products has undoubtedly revolutionised equine sport and veterinary medicine. Equally, these ever-progressing advances have highlighted the importance of enforcing strict biosecurity and hygiene practices.

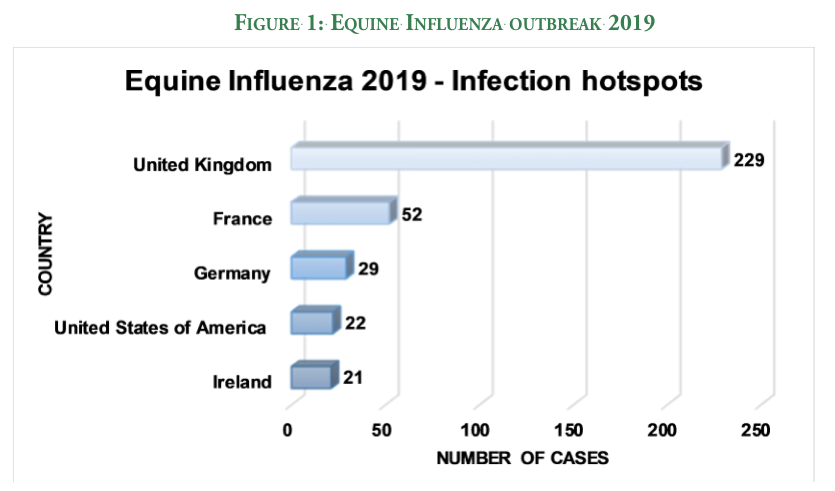

The efficient movement of horses and biological products has undoubtedly revolutionised equine sport and veterinary medicine. Equally, these ever-progressing advances have highlighted the importance of enforcing strict biosecurity and hygiene practices. The February 2019 equine influenza outbreak (figure 1) reminded us of the impact of contagious disease on equine sport and movement. British racing authorities acted swiftly to minimise disease spread, temporarily suspending several race meets. Further precautionary measures were taken to lockdown stables who had confirmed cases and potential recent contacts. The six-day suspension was lifted following successful disease containment, resulting from the collective effort of all stakeholders in adhering to biosecurity and vaccination rules as laid out by racing authorities.

Research from Dominguez et al (2016) identified that several infectious diseases relating to ‘disease events’ were a result of international horse movements2; these included equine infectious anaemia (EIA), contagious equine metritis organism (CEM), and equine viral arteritis (EVA).

Equine venereal disease has been associated with significant economic losses due widespread abortion in mares, neonatal death and identification of the carrier horse3,4. Timoney et al. 2011 stated that the estimated cost of the 1978 Kentucky CEM outbreak was $1,000,000 for each day equine movement restrictions were in place, preventing all breeding4. The impact of these outbreaks clearly demonstrates the value of implementing testing and prevention protocols which act as a type of biosecurity ‘insurance’ for equine populations.

The Horseracing Betting Levy Board (HBLB) published the 42nd edition of the International Codes of Practice 2020 in January this year5. This code provides voluntary recommendations to breeders regarding the prevention and control of specific equine diseases, including but not limited to CEM, EVA, and EIA. These recommendations are common to Ireland, Germany, France, Italy, and the UK, but have been adapted and implemented by numerous countries worldwide, particularly following the development of the EquiBioSafe application for iOS and android smartphones.

CEM, EVA, and EIA are listed as notifiable diseases by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). This means that by law, a positive test confirming infection must be reported to the relevant country’s governing department by the horse’s owner, manager, veterinary surgeon, or diagnostic laboratory concerned. The department will then make a ruling with regards to the appropriate control measures which may include movement and/or breeding restrictions, and notifying the OIE... To read the complete article you need to be a subscriber

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO BREEDING NEWS

SUBSCRIBERS CAN READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE BY LOGGING IN AND RETURNING TO THIS PAGE

Equine Arteritis Virus

Equine Arteritis Virus (EAV) is the causative agent of the disease Equine Viral Arteritis (EVA). The disease was first detected on a Standardbred stud in the United Stated in 1953, where many subsequent outbreaks have caused substantial economic losses3. EVA now circulates widely on continental Europe due to the unrestricted movement of stallions within the European Union. The virus is transmitted via respiratory secretions, natural, and artificial venereal contact. Thus, the disease is easily spread in non-breeding animals once present on equine premises. In 2019, the UK reported an outbreak caused by suspected respiratory transmission linked to attendance at a competitive equine event6. Disease presentation is variable, ranging from asymptomatic to abortion in pregnant mares and death in young foals. Clinical signs may include fever, depression, reduced appetite, and inflammation of conjunctiva (‘pink eye’), among others.

EAV establishes persistent infection in the reproductive tract of 10-70% of all infected carrier stallions7, rendering many breeding stallions’ permanent carriers or ‘shedders’ of the virus through their semen. This occurs without a reduction in fertility or other clinical signs7. For these reasons, vaccination of breeding stallions and teasers is highly recommended. The HBLB Code of Practice 2020 states that the best method of prevention is ensuring the stallion is disease-free prior to the commencement of any breeding activities8. This is completed through a blood test, checking for the presence of specific antibodies – serological testing. A seropositive result indicates an active infection OR previous infection OR vaccinated horse. Thus, a ‘shedder’ will have the same testing result as a stallion who has been vaccinated against the disease8. In order to prove that the stallion is not a shedder, the owner must complete a blood test prior to the vaccination and retain the previous seronegative result, usually marked in the passport by a veterinarian. The existing European recommendations suggest that stallions should receive a vaccination on a six-monthly basis. Otherwise all unvaccinated stallions should be tested after January 1 of the new year and only commence breeding activity on receipt of a seronegative result8.

There are comparatively fewer guidelines in relation to mares; generally guided by the mare’s history, contact with other animals, and the overseeing veterinary surgeon. However, the Code of Practice 2020 suggests that the mare should be tested, at minimum, after January 1 that year, and 28 days prior to any breeding activity, regardless of the method (artificial/natural insemination)8. The mare should not be included in any breeding programme until the results are confirmed as seronegative. If the mare is found to be seropositive for EVA she must be isolated immediately, this also requires the isolation and testing of any equines she has been in contact with. Re-testing should occur at minimum 14-day intervals; a return to breeding is guided by a veterinarian following stabilisation or a decline in blood circulating antibodies.

Contagious equine metritis organism

Contagious equine metritis organism (CEM/CEMO) is a venereal disease caused by the bacterium Taylorella equigenitalis. CEM is highly contagious and can be difficult to detect and control as equines may be asymptomatic. The disease was first identified in Newmarket in 1977 but has since been eradicated from the UK.9 However, the disease circulates widely in mainland Europe where currently there is no vaccination to prevent CEM9. Due to seasonal equine breeding practice, CEM can have a devastating effect on equine reproductive efficiency. Infection causes vaginal discharge and infertility in mares, however, there are no outward clinical signs of disease in infected stallions or carrier mares. The disease is spread through natural and artificial breeding practice, or indirectly via staff hands or infected semen collection equipment.

As with EVA, the best method of prevention is ensuring the equine herd is free from disease prior to any breeding activity. Testing for CEM occurs through swabbing the genitalia of mares and stallions for culturing and analysis in a specialist laboratory. If a positive result is returned, the horse must be treated and re-tested prior to being cleared for breeding9. Equines should be tested after January 1 and before breeding activity to rule-out any infection. The HBLB Code of Practice 2020 provides a detailed list of recommendations with regards to mare/stallion at-risk status and testing protocols. Further to this they recommend appropriate training in hygiene and biosecurity for breeding and stable staff to prevent indirect transmission9.

Equine Infectious Anaemia

Equine Infectious Anaemia (EIA) is often called ‘swamp fever’ due to its prevalence in warm, wet areas and is caused by the equine infectious anaemia virus (EIAV). Disease transmission occurs through the transfer of blood or secretions containing infected cells, biting flies, contaminated needles, teeth rasps, stomach tubes, twitches, or any other instruments which may cause abrasion. The virus occurs worldwide across all equine population groups. Clinical signs, as in EVA and CEM, are extremely variable; ranging from asymptomatic to fever, ataxia, haemorrhaging, and increased respiratory and heart rate, among others10.

In 2006 there was a cluster of positive cases detected in Ireland originating from the use of infected plasma11. It is estimated that the Irish Equine Centre completed 57,000 tests in the process of returning Ireland to disease-free status11,12.

A similar but much larger outbreak occurred in Germany in 2012, where contaminated donor blood was linked to over 900 horses12. There are currently no vaccinations to prevent EIA, where infected horses remain carriers for life. Thus, the only form of prevention is through serological testing (blood testing) and ensuring a negative result on an annual basis. The Coggins test is deemed the clinical gold standard and used to confirm infection/infection absence12. The ELISA for EIA test is used to screen the population where EIA is not suspected12.

The HBLB code of Practice 2020 advises that if a horse displays severe unexplained anaemia; they should be isolated and tested for the disease as soon as possible10. Stallions should be tested following January 1 each year; mares should also be tested after January 1, but within 28 days of breeding. Disease eradication involves identifying infected horses and compulsory removal (slaughter) from the population.

Screening and prevention recommendations

• Horses must be tested annually - after the 1st of January and before any breeding activities are completed

• Equines should be vaccinated where possible/available

• Stallion owners should implement an annual screening programme and insist on dated EVA, EIA and CEM certificates from each mare owner

• Equally, mare owners should request proof regarding the stallion’s screening record

• If a mare does not fall pregnant following covering by a selected stallion, and the owner wishes to change stallion, the owner must provide a new set of EIA, EVA and CEM clearance certificates

• All tests must be completed and documented by a veterinary surgeon

•Tests must be analysed at a specialist laboratory

• All imported blood/breeding products should be tested

• Breeding/Stable staff should be trained in biosecurity and appropriate hygiene practice to prevent disease spread.

For more information regarding prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment of notifiable diseases please see the HBLB Code of practice 2020 and the OIE website.

References

1. Animal health trust, Equine influenza outbreaks reported in 2019, available online at: https://www.aht.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Equiflunet-outbreaks-to-15-April-2019.pdf

2. Dominguez, Morgane, et al. "Equine disease events resulting from international horse movements: Systematic review and lessons learned." Equine veterinary journal 48.5 (2016): 641-653.

3. Balasuriya, U. B. R., M. Carossino, and P. J. Timoney. "Equine viral arteritis: a respiratory and reproductive disease of significant economic importance to the equine industry." Equine Veterinary Education 30.9 (2018): 497-512.

4. Timoney, P. J. "Horse species symposium: contagious equine metritis: an insidious threat to the horse breeding industry in the United States." Journal of animal science 89.5 (2011): 1552-1560.

5. HBLB International Codes of Practice 2020, Home, Available at: https://codes.hblb.org.uk/

6. HBLB International codes of Practice 2020, Equine Viral Arteritis – EVA, Available online at: https://codes.hblb.org.uk/index.php/page/30

7. Carossino, Mariano, et al. "Equine arteritis virus elicits a mucosal antibody response in the reproductive tract of persistently infected stallions." Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 24.10 (2017): e00215-17.

8. HBLB International codes of Practice 2020, Equine Viral Arteritis – EVA, Prevention, Available online at: https://codes.hblb.org.uk/index.php/page/53

9. HBLB International codes of Practice 2020, Contagious Equine Metritis -CEM, Available online at: https://codes.hblb.org.uk/index.php/page/19

10. HBLB International codes of Practice 2020, Equine Infectious Anaemia - EIA, Available online at: https://codes.hblb.org.uk/index.php/page/33

11. Cullinane, A., et al. "Diagnosis of equine infectious anaemia during the 2006 outbreak in Ireland." Veterinary Record 161.19 (2007): 647-652.

12. Roberts, Helen. "Equine infectious anaemia in Europe: an ongoing threat to the UK." Veterinary Record 181.17 (2017): 442-446. n